By MATEUSZ PERKOWSKI

(Salem) Capital Press

FOREST GROVE, Ore.– Staring into the placid depths of Hagg Lake, farmer and forester Hank Scott sees more than a 50,000-acre-foot reservoir.

Beneath the lake’s surface once stood a handful of homes, a church, a grade school Scott attended as a boy, as well as his family’s dairy farm.

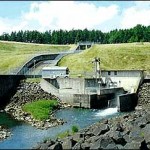

Scott’s father fought to save the farm and the surrounding valley from flooding, but ultimately lost that battle when construction of the Scoggins Dam concluded in 1978.

The family relocated to a property uphill from the lake, where they now raise timber and Christmas trees, and put the ordeal behind them.

“We thought we were done with it,” said Scott.

As it turns out, the Scoggins Dam project only temporarily sated the region’s thirst for irrigation and municipal water. It now appears the lake will continue encroaching on land owned by the Scotts and other families in the region.

Washington County, where the dam is located, is already the second most populous county in Oregon and will likely continue expanding in the coming decades.

To forestall conflict between urban, rural and environmental interests, Clean Water Services – the agency that oversees storm and waste water management in the region – plans to double the reservoir’s capacity to meet water demands through 2050.

By raising Scoggins Dam 40 feet, Clean Water Services and local municipalities expect to increase storage in Hagg Lake by another 50,000 acre feet and dodge the fate of other water-starved regions like the Klamath Basin.

“We’re trying to avoid that,” said Tom VanderPlaat, water supply project manager for Clean Water Services.

It may be hard to believe that any region in notoriously wet Western Oregon could have problems with insufficient water, but that’s what initially inspired the development of Scoggins Dam.

Since the 1930s, the region had been alternatively plagued by flood control problems during winter and deficient water supplies during the summer, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Currently, the reservoir provides enough water for 17,000 acres in the Tualatin Valley Irrigation District. In the 1950s, only a third of that area was adequately irrigated, according to the bureau.

The Scoggins Valley was first analyzed as a potential reservoir site in 1956, about 10 years before the project was authorized by the federal government and more than 20 years before it was completed.

The proposal to raise the dam appears to be moving at a similar pace. It has been roughly a decade since water managers in the region identified the need for increased water supplies and nearly 5 years since they designated dam-raising as a feasible option.

In 2009, the planning phase of the project is expected to end, which means Clean Water Services and its partners will need to make important commitments to get the project to the finish line, said Mark Jockers, spokesman for the agency.

“We’re getting to that stage where there are going to be some tough decisions to make,” said Jockers.

For starters, the idea to simply use the existing dam as a foundation for an additional 40-foot earthen structure will probably not pass muster due to potential instability during an earthquake, said VanderPlaat.

That means a new structure will need to be built either directly below the existing dam – rather than on top of it – or farther downstream. In either case, the structure will probably need to be built with rock fill and concrete instead of earth from nearby hills, as originally planned.

“We haven’t figured out where those rock sources are,” said VanderPlaat. “We know they’re not right near the site, so we’ll be looking some distance away.”

Final plans for raising the dam, revised to account for seismic safety, are expected to be done by June 2009, with more precise cost estimates.

Currently, the dam-raising alone is estimated at $260 million, with total project costs – including new pump stations, roads and other ancillary ventures – expected to top $500 million.

“My guess is they’re not coming down,” said VanderPlaat.

To bypass cumbersome federal regulations, Clean Water Services and its municipal partners want to take over ownership of the dam from the Bureau of Reclamation. That means most of the project’s price tag would need to be covered by local authorities, not the federal government.

These local governments would also assume the liability for anything that goes wrong with the dam, such as a disastrous breach. Even if they decide to assume the risk, the title transfer would need be approved by an act of Congress.

“These processes take a long time,” said VanderPlaat.

If the project moves ahead as planned, the dam raising would be complete by 2016, though VanderPlaat acknowledges that is a very optimistic timeline.

“I’m probably going to get a big star if I do that,” he said.

In the meantime, Scott and 13 other landowners in the vicinity of the lake have to live with the knowledge that a portion of their property may eventually be submerged.

VanderPlaat realizes the looming possibility is disturbing to them, but nonetheless believes in keeping the planning process as transparent as possible.

It is better for landowners to brace for the future instead of being caught by surprise, he said. “I really don’t want somebody to come and say they didn’t know.”

Even though Scott stands to lose one-fifth of his 200 acres to Hagg Lake, he doesn’t plan to fight the project.

Though he can’t help feeling melancholy about forfeiting family landmarks, such as a log cabin he helped build as a boy in 1940, Scott said the region’s growing demand for water is an undeniable reality that has to be addressed eventually.

“I don’t think it does any good to be against it,” he said.

© 2009 Associated Press. Displayed by permission. All rights reserved.

You may forward this article or get additional permissions by typing http://license.icopyright.net/3.5721?icx_id=D95GKT900 into any web browser. Press Association and Associated Press logos are registered trademarks of Press Association. The iCopyright logo is a registered trademark of iCopyright, Inc.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.