By Dave Kranz

California Farm Bureau,

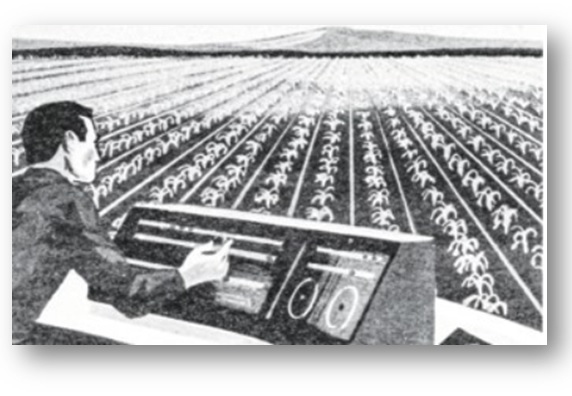

“The heart of the farming operation of the future may very well be a control center equipped with a wide array of electronic wizardry,” reads the description on this illustration from a 1969 Farm Bureau Monthly article previewing agriculture in the 21st century. –Graphic/Ford U.S. Tractor and Implement (1969)

To commemorate the California Farm Bureau Federation’s 50th anniversary, in 1969, the CFBF publication Farm Bureau Monthly set out on a bold project: predicting what agriculture would be like 50 years in the future.

The publication consulted experts from many sectors and aspects of agriculture, publishing more than two-dozen articles in five consecutive issues. Their predictions involved not just how farmers would farm, but how people would live their lives, buy food and communicate.

They may or may not have expected someone to dig out their forecasts 50 years later but here’s the thing: Many of their predictions turned out to be prescient.

Sure, there was some “Jetsons”-style speculation. A professor of family life predicted we’d be eating off of plastic dishes that after use would be placed in a machine that would clean, melt and remold new dishes; that closets would be outfitted with devices to clean clothes by sonic waves; and that giant hovercraft would carry passengers and freight.

But a representative of Safeway Stores predicted people would shop by video phone, with charges to the shopper’s credit card automatically deducted from the bank account. A University of California agricultural scientist accurately foresaw an upcoming era of instant communication.

When it came to predicting what 21st century farming would look like, many writers focused on the promise of computers and mechanization.

“Farming will be a miracle of mechanization, chemistry and management skills,” wrote Ralph Bunje of the California Canning Peach Association.

Other writers tempered their expectations of how machines would change agriculture.

An American Farm Bureau Federation policy specialist, Matt Triggs, believed new machinery and equipment would perform an increasing proportion of total work, “but for a long time, human labor, even at much higher than existing wage rates, will be cheaper and more satisfactory than machine operation for a few agricultural operations.”

A subtropical horticulturalist for the UC Extension Service, Robert G. Platt, said he expected citrus mechanization and automation to come with future plantings, but “whether complete mechanization of harvesting ever becomes a reality remains to be seen.”

Platt accurately foresaw an “inevitable” reduction in Southern California citrus acreage as the region urbanized, and other writers also warned of forces they expected to challenge agricultural production.

An extension economist at UC Riverside, William W. Wood Jr., said if 1969 land-use trends continued, there would be “virtually no prime land available for agricultural production 50 years hence.”

Competition for water would also intensify, according to AFBF natural resources director Clifford G. McIntire: “Agriculture must be vigilant or it will be outbid, outmaneuvered or out-legislated in the competition for present and future water resources.”

The peach association’s Bunje expected additional oversight: “Government will regulate the use of chemicals, water drainage and the environmental operation of farming. Farming will be governed by laws relating to natural resources.”

Farmers and ranchers would also need to adapt to new marketing realities, wrote UC agricultural economist G. Alvin Carpenter: “Farmers, as well as their marketing agencies, must either act to shape the future, or they must defensively react as they rebound from crisis to crisis.”

The livestock business in 1969 faced a variety of problems, UC Extension animal scientist J.T. Elings wrote: land prices, taxes, diseases and imports, plus “imitation milk and ice cream, soybean hamburger, plastics instead of leather, synthetic fibers instead of wool.”

“Whether the animal industry survives will depend on its ability to change—to adapt,” Elings wrote.

That adaptation would depend on versatile, well-educated farmers and ranchers, according to J.J. Miller of the Agricultural Producers Labor Committee.

“By 2000 the farmer will have developed the talents of a Renaissance man of many parts to succeed in the agricultural arena,” Miller wrote. “More than a smattering of knowledge in the fields of finance, chemistry, horticulture, meteorology, business management, psychology, engineering, to name a few, will have to be at his command.”

CFBF leaders also wrote about the future of the Farm Bureau organization—we’ll share their thoughts in a subsequent edition of Ag Alert®—and UC Vice President J.B. Kendrick Jr. said Farm Bureau should take pride in how agriculture had advanced during its first 50 years.

“When this organization celebrates its centennial anniversary,” Kendrick wrote, “I am certain that the accomplishments of the second half of the century will be even more exciting, more unbelievable, and more satisfying to mankind.”

(Dave Kranz edits Ag Alert® and is director of publications and media relations for the California Farm Bureau Federation. He may be contacted at [email protected].)

Permission for use is granted, however, credit must be made to the California Farm Bureau Federation when reprinting this item.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.